How Can a small Farm "Compete" Against a BIG Farm

What can your farming neighbor teach you about your alpaca farm? I found many answers about livestock business planning and went no farther than my "backyard."

What can your farming neighbor teach you about your alpaca farm? I found many answers about livestock business planning and went no farther than my "backyard."

I live in rural south-central PA, previously one of the top counties in the state for agriculture and most specifically for dairy farms and fruit orchards. Forty years ago, everyone in the dairy business Forty years ago, everyone in the dairy business followed the same business plan. Most milked a herd of 150-300 head per day, grew their hay and crops and sold their milk directly to a general buyer. There was a local farm veterinarian that would make calls for milk fever and calvings. Most farmers used the same reliable bull or contracted with a neighbor to use their animal. AI and Frozen Embryos were not part of our everyday vocabulary.

Fast forward to 2018; now you will find five different business models for dairy cows in less than a five-mile radius of our farm. Three of the farms are commercial, one is a cottage, and one is a combination of the commercial and cottage industry. These farms vary considerably regarding size, objectives, daily operations, income/expense, etc. What you might find interesting is how the SIZE of the farm (as defined by the number of animals) is directly related to the number of farms that practice the same business model. In other words, you will find far more sizeable commercial dairy farms whose end product is milk production, than you will see small gene pool/seed stock production. That’s a critical point as we compare principles of the dairy industry to our alpaca industry. Although the majority of alpaca farms in the US are small in animal numbers and follow business models which better align with a cottage industry model, many small alpaca farmers consider alpaca animal sales as critical to their income.

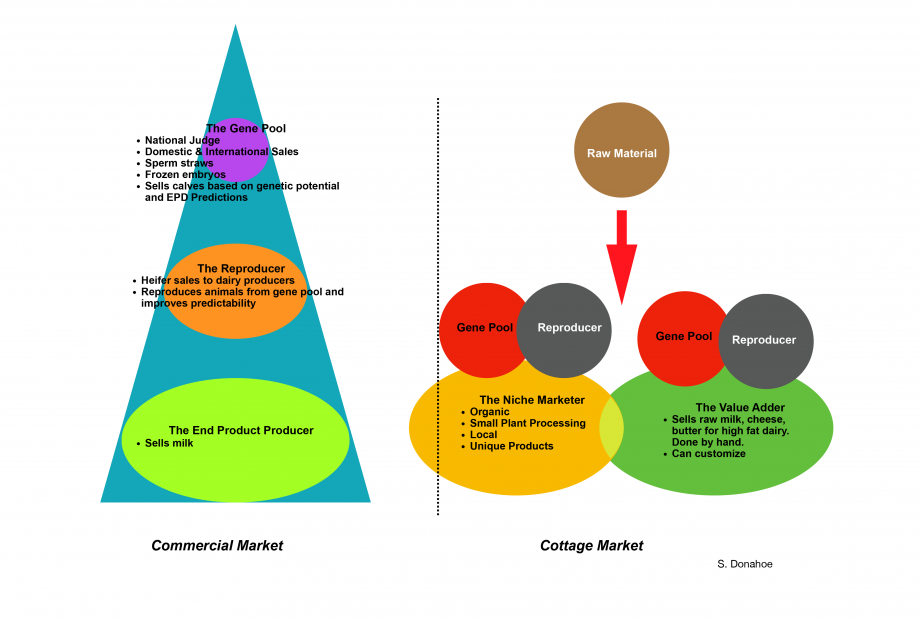

I visited these area dairy farms and created names for them based on their business purpose. In the image below, the three dairy farmers who are exclusively in a commercial market, have cash-based sales and they do not add value to their end product. A fourth dairy farm is a cottage industry farmer, which means that this farmer value adds to the raw material, thereby increasing its sales price (but also there is an increased cost to production). The cottage industry dairy farmer in this example operates their business as a cash sale, although other cottage industry farmers might turn a product sale, which we see more commonly in the alpaca business. The fifth dairy farm is a combination of commercial and cottage, whereas the business plan they follow value adds to the raw material and has a cash sale, but it ’s successful is heavily vested in the niche market.

In comparing the commercial business plan to the cottage business plan, it’s worthy to note differences in how the two approach breedings for their herd regarding specifics, goals, and outcomes. Commercial businesses work to create a uniform commodity, one that is highly reproducible and predictable. Cottage businesses base their work on uniqueness and artistic creativity. Commercial farmers rely on and depend on records and a workable EPD system to make breeding decisions to produce improved results (as established by goals and objectives). Cottage farmers are not limited by reproducing results and are preferably rewarded for their differences in production. Maintaining records and EPD predictive scores is not as critical to the cottage producer, and therefore, there is less reliance on seeking outside seed stock/gene pool producers.

Below is a schematic diagram of how I perceive the branches of a livestock business. Noteworthy in this diagram is that these are parallel branches, rather than one being of greater importance than the other.

The Gene Pool/Seed Stock Producer

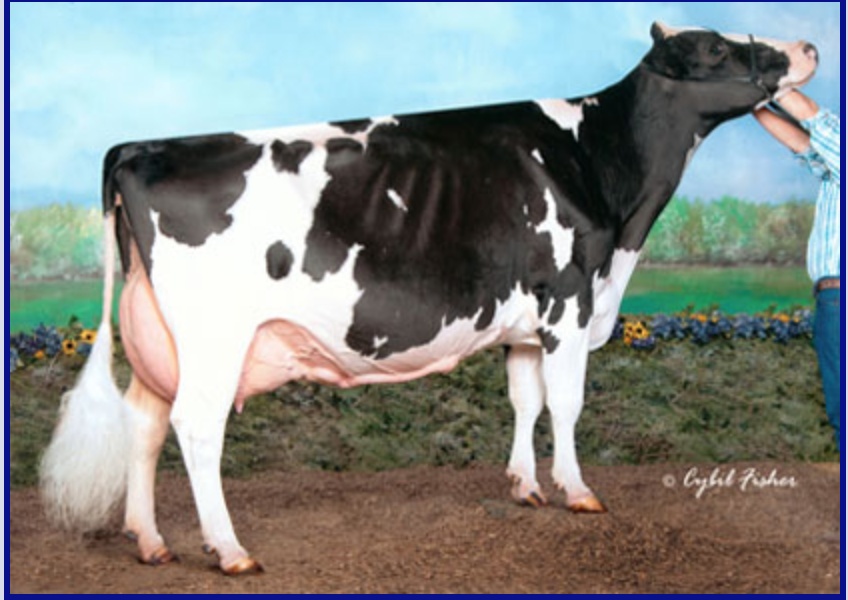

The Gene Pool/Seed Stock Producer The gene pool/seed stock producer is the smallest of the dairy farms and is a farm you wouldn’t notice unless you were specifically looking for it. This farmer manages a dairy herd of 100 or less and their primary product is the sale of calves, semen straws, and frozen embryos. The farmer is a national judge, and t h e y h a v e f r e q u e n t international visitors to their farm, paying upwards of $35,000 for a six-month-old calf that shows potential. A heifer can sell for 1 million dollars and the buyer will hope to recoup that in embryonic flush sales. This gene pool/seed stock producer is akin to how most alpaca farmers define their business in the US. Most will place alpaca animal sales as their number one commodity, and most promote it through advertising and participation in alpaca shows to that end purpose.

The Gene Pool/Seed Stock Producer The gene pool/seed stock producer is the smallest of the dairy farms and is a farm you wouldn’t notice unless you were specifically looking for it. This farmer manages a dairy herd of 100 or less and their primary product is the sale of calves, semen straws, and frozen embryos. The farmer is a national judge, and t h e y h a v e f r e q u e n t international visitors to their farm, paying upwards of $35,000 for a six-month-old calf that shows potential. A heifer can sell for 1 million dollars and the buyer will hope to recoup that in embryonic flush sales. This gene pool/seed stock producer is akin to how most alpaca farmers define their business in the US. Most will place alpaca animal sales as their number one commodity, and most promote it through advertising and participation in alpaca shows to that end purpose.

Windy Knoll View’s webpage speaks very little to it’s operation, but instead focuses on their genetic lines and sales, similar to what we post through OpenHerd and other websites. They are very active in their national organization and showing is an integral part of their business. Their veterinary costs per animal are much higher than an end producer farm. The Reproducer The Reproducer is not as prevalent in my area of the country. This farmer maintains a midsize farm and works between the Gene Pool Provider and the End Product Producer.

Windy Knoll View’s webpage speaks very little to it’s operation, but instead focuses on their genetic lines and sales, similar to what we post through OpenHerd and other websites. They are very active in their national organization and showing is an integral part of their business. Their veterinary costs per animal are much higher than an end producer farm. The Reproducer The Reproducer is not as prevalent in my area of the country. This farmer maintains a midsize farm and works between the Gene Pool Provider and the End Product Producer.

The Reproducer

The Reproducer is most interested i n replicating the gene pool offspring, focusing on consistency and predictability, so that he/she may then sell those offspring to the End Product Producer, but at a lower price. The gene pool producer has invested more money per animal into producing an improved and elite offspring. The replicator takes what he/she learns from the gene pool, purchases the semen straws, embryos, and/or calf, and then uses them in his/her herd to produce offspring for the end product producer. For the reproducer, the cost and time-vested per animal are much less. The reproducer works to keep costs down by operating similar to a end product producer. Their income comes from two sources, milk production, and calf sales.

The Reproducer is most interested i n replicating the gene pool offspring, focusing on consistency and predictability, so that he/she may then sell those offspring to the End Product Producer, but at a lower price. The gene pool producer has invested more money per animal into producing an improved and elite offspring. The replicator takes what he/she learns from the gene pool, purchases the semen straws, embryos, and/or calf, and then uses them in his/her herd to produce offspring for the end product producer. For the reproducer, the cost and time-vested per animal are much less. The reproducer works to keep costs down by operating similar to a end product producer. Their income comes from two sources, milk production, and calf sales.

The End Product Producer

The End Product Producer would have the largest of farms regarding acreage and number of animals. The cost per calf is the lowest of the three commercial producers. This farmer has a very high volume of end product sales with minimal costs involved in the production. Compared to the gene pool/seed stock producer, this farmer's veterinary costs are lower, and this farmer's primary reason for veterinary consult is for necessary testing and consult on herd management, rather than for an individual animal health issue.

Mercer-Vu Farms is a modern, third generation, family owned, and operated dairy farms in Mercersburg, Pennsylvania and in Whitepost, VA. They milk a total of 2500 cows and have approximately 300 dry cows. In addition, there are 2500 head of young stock that they raise yearly. Mercer-Vu Farms produce 25,000 gallons of milk per day. They farm about 4000 acres to provide feed for their animals, double cropping rye and triticale with corn and alfalfa. Mercer-Vu Farm puts up 40,000 tons of corn silage, 6000 tons of alfalfa, 8500 tons of rye/ triticale and 70,000 bushels of corn yearly. They employee 46 full time employees and several part time employees and positions include milkers, mechanics, truck drivers, herdspeople and others. Mercer-Vu Farm’s primary source of income is from raw milk sales. Out of necessity, they sell their steers once they hit 400 pounds. Their veterinary bills are primarily for herd management, and they calculate to be $100 per animal per year, which includes any and all medical care, other than AI. Their AI cost are between $9 and $33, depending on if they semen straw is sexed and they purchase from a “Reproducer” Farm. They monitor their operation by following the total costs per 100 pounds per milk. None of their herd is registered, although they keep an extensive data base and records on their herd. They are not involved in a national organization, other than to be active in government policies that would affect their business. They do not show, other than the few 4-H cows owned by their children. Of interest if their observation that the show ring does not honor the traits that they feel are important to end production, and they cite examples such as tall stature and fine frame as two examples.

The Value Adder

It's interesting that this is where most persons in the US alpaca industry practice their business model. Most alpaca farms take raw fiber and turn it into various products, from rovings to sweaters. By adding value to the raw material, the end sale will increase exponentially. But value adding can come with a downside if a farmer needs to outsource at every step in production and their income will be considerably reduced as a result. Value adding requires more work to produce the end product, and most people think it is a small-scale operation. However, for this dairy farm, it is a substantial production whereby other farms contribute, and this diversity brings in more buyers. Their method to keep costs down is to co-op expenses and even sales and they use diversification i n t o o t h e r m a r k e t s a s a successful strategy.

It's interesting that this is where most persons in the US alpaca industry practice their business model. Most alpaca farms take raw fiber and turn it into various products, from rovings to sweaters. By adding value to the raw material, the end sale will increase exponentially. But value adding can come with a downside if a farmer needs to outsource at every step in production and their income will be considerably reduced as a result. Value adding requires more work to produce the end product, and most people think it is a small-scale operation. However, for this dairy farm, it is a substantial production whereby other farms contribute, and this diversity brings in more buyers. Their method to keep costs down is to co-op expenses and even sales and they use diversification i n t o o t h e r m a r k e t s a s a successful strategy.

Pennland Pure is a farm owners collaborative in this region. It’s members have agreed to treat their land and livestock with respect and take passionate pride in purveying products of the highest quality. Their cheeses are made simply and sustainably from the highestgrade dairy products. There are 650 farmers who participate in the cooperative and they share a commitment to a way of dairy farming that focuses on producing products of very high standards. As members of the FARM program, all of our dairy co-op partners closely follow a set of guidelines for providing the highest standards of animal care, land management and product handling to ensure the excellence of their milk and the future of their farms.

I did not interview Pennland Pure, but there are a number of local dairy farmers that belong to the program. Most maintain small herds on lesser acreage. Because they sell a product with high standards, they are able to demand a higher price for their end product. There are also many artisan farms locally that rather than sell raw product to a cooperative, they value add by making artisan cheeses and butter and sell directly to the public.

The Niche Marketer

Many of the family dairy farms that have been passed down from generation to generation are going out of business. Hopefully, some will revise their business plans to include a niche market. It is increasingly difficult to sell raw milk at today's milk prices and compete with the large end product milk producers. The cost of running a farm is incredibly high, and even with government subsidies, many are not staying in business. This particular farm sells both wholesale and retail. It has grown to the point that it buys raw milk from other organic and/or grass-fed milk producers. They have a wide variety of valueadded products that they sell both wholesale and retail, such as ice cream, butter, cheese, grass-fed beef and this operation has restaurants at their factories where customers can enjoy a meal while watching the processing of milk.

Trickling Springs Creamery aims to produce fresh, exceptional-tasting dairy products while promoting local farmers doing an excellent job with their farms. The founders started by establishing strict guidelines for the family farms producing their milk. The farmers were required to maintain grass-fed, heritage breed cows, produce very clean milk (as measured by SCC & SPC counts), and use no synthetic hormones. The founders offered to pay farmers above average prices for maintaining these high standards. Trickling Springs Creamery would then process the milk as minimally as allowed by law.

Trickling Springs Creamery launched a Farmer-for-Life™ program to encourage farmers to make the transition from conventional farming to organic farming. This program incrementally pays farmers for each step they make along the journey toward being Non-gmo Project Verified® and certified organic. Currently they purchase milk from 32 farms.

Their products include organic bottled milk in either returnable glass or plastic bottles, grass-fed milk, butter, cheese, ice cream as well as these same products in grass fed non-organic form. They operate two restaurants, one in Chambersburg, PA and one in Washington, DC.

Most of the contributing farms are medium in size, averaging 300 acres of farm land, crop production, and grazing and maintaining a herd of 200-500 cows. Animals are rotationally managed on pasture, grazing one section of pasture at a time, before they are moved on to fresh ground.

Trickling Springs Creamery is not active in a national organization, but instead maintains many certifications and rather than show animals, they showcase their products which have received numerous awards.

I started writing this blog because there are so many things we can learn from other livestock farming models and we as an industry have not taken advantage of these farming operations. I hear many comments from my peers who share a similar belief that the "small" farm does not have a voice. I offer you an alternative way to view your alpaca business. Rather than large farm--small farm, perhaps we would be better served to label ourselves as commercial farm-- cottage farm--combination commercial cottage farm.

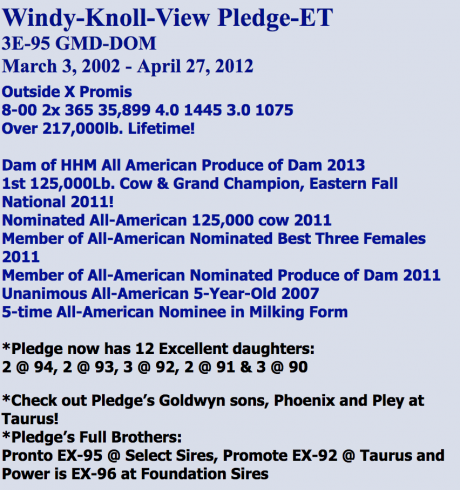

Below is a schematic drawing of alpaca business model examples.

I hope this writing has helped to dispel the following alpaca farming myths.

• A successful alpaca farm is a large farm • Small farms compete with large farms.

• Commercial farms and cottage farms have similar objectives and goals.

And instead, has triggered thoughts as to the following possibilities for our alpaca industry.

• The size of the farm is NOT the defining point in our alpaca industry.

• We should not have shows based on small, medium, and large farm parameters. They use different business models.

• We should not have AOA BOD as representative of small farms versus large farms, but instead, we need representation of commercial and cottage industries.

• We should not be pitting the small farm against the large farm.

It remains my belief that the majority of people in the alpaca business do not have livestock experience, nor have we owned and operated a business. I do not mean to label this as good or bad....it merely is. Many of us, myself included, entered this venture with the expectations that we will learn as we go, we will follow our mentor's advice, and that we will practice one business model and path for our alpaca industry. Years later, I recognize the falsity of my earlier beliefs, and now I believe there are always alternatives to the status quo.

For further discussion, see this post and others in Facebook Groups Farmers and Ranchers Facebook Group–Farmers and Ranchers. Join in to make a difference.